Chicago’s mayor can pick the aldermen. That's a problem.

Chicago is the only big city in the nation where the mayor fills vacancies in City Council.

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson is about to create his first alderman.

On Feb. 28, he named his top ally in the City Council, 35th Ward Ald. Carlos Ramirez-Rosa, to the top post in the Chicago Park District.

That means Johnson now has the privilege of selecting Ramirez-Rosa’s successor – continuing a long tradition of Chicago mayors who fill City Council vacancies.

The mayor’s likely pick is Cook County Commissioner Anthony Quezada, who announced this week he will “seek the community’s support via the mayor’s formal appointment process.” But Johnson hasn’t told reporters what that process entails.

Chicago is the only big city in the nation that functions this way. And it’s a problem.

How Chicago fills vacancies

In Chicago, virtually all City Council vacancies are filled by the mayor with consent of the City Council.

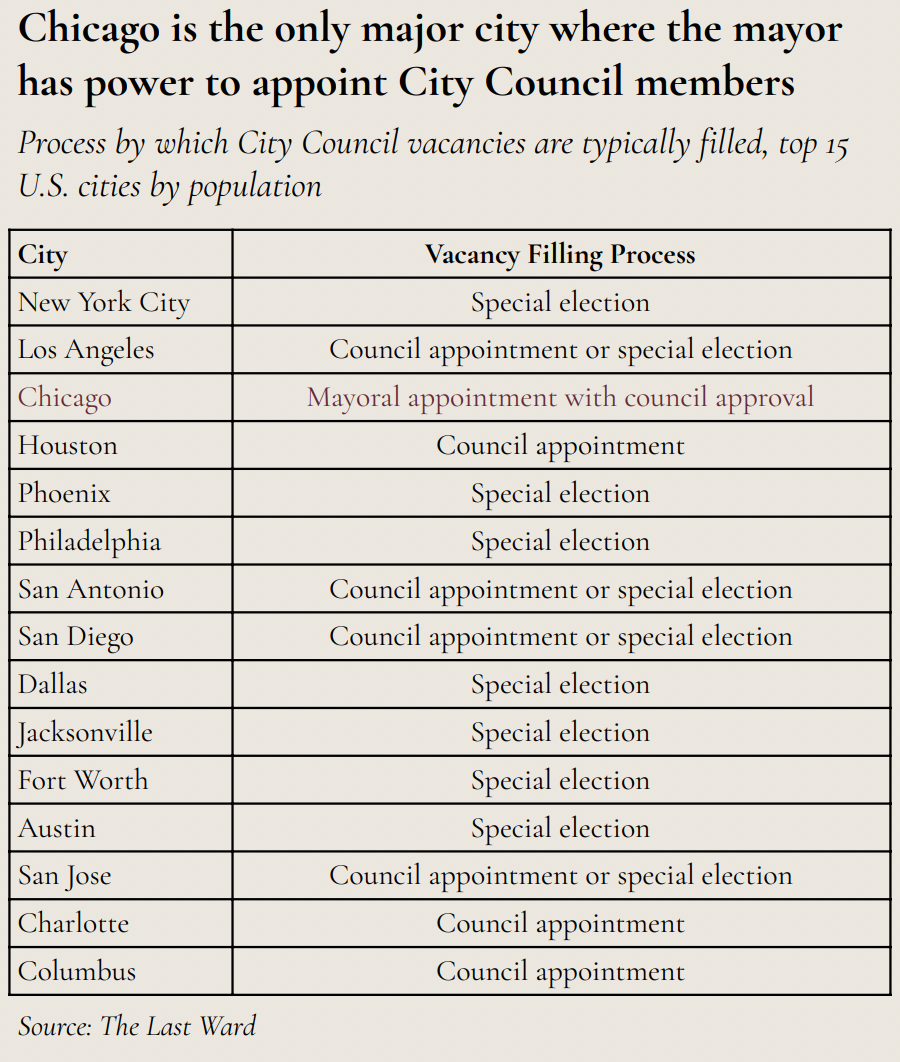

This is unheard of in other major U.S. cities.

Among the top 15 by population, only Chicago gives the mayor authority to fill vacancies. Instead, the most common process for filling Council vacancies is via special election.

Why is Chicago such an outlier?

For one, because Chicago’s process for filling vacancies rests in Illinois state law. Every other major city lays out this process in their respective city charters.

But Chicago is the only major city in the country without a charter.

To learn more from local and national experts about how Chicago can create a city charter, register for the March 24 Chicago Charter Symposium at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law.

Charter or not, there are good reasons why other cities don’t grant their mayor the power to fill vacancies.

Here are two:

It gives the executive branch too much power over the legislative branch of city government.

It discourages democracy.

No one mayor should have all that power

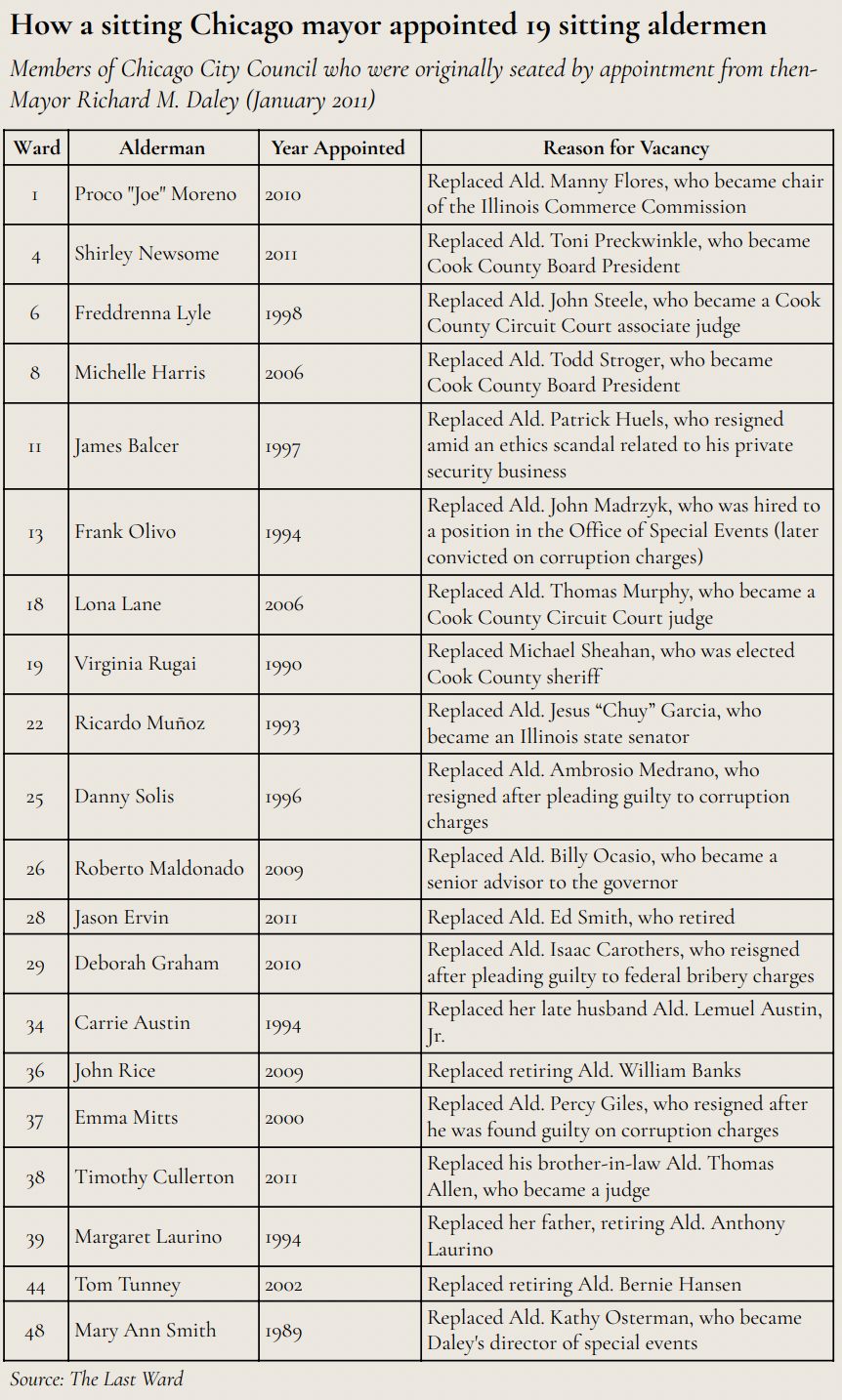

Not long ago, Chicagoans lived in a city where the sitting mayor handpicked more than a third of the City Council.

Just five years into his term in 1994, 15 of the 50 sitting aldermen and the city clerk were originally appointed by Mayor Richard M. Daley.

By the end of his term, 19 of the 50 sitting aldermen owed their start to the mayor’s appointment power.

That’s not a typo.

Johnson picking Ramirez-Rosa’s successor after placing him elsewhere in city government is nothing new.

Daley named sitting Ald. Kathy Osterman as his director of special events and then appointed Mary Ann Smith as his successor. Smith would go on to win re-election four times and serve for 20 years. He also hired Ald. John Madrzyk to a position in the Office of Special Events and named Frank Olivo as his successor. Madrzyk was convicted on corruption charges related to his work in City Council – Olivo went on to hold that office for 17 years, and was most recently in the news for taking a $4,000-a-month no-show job as part of the ComEd bribery scandal.

With a sizable bloc of City Council owing their jobs to the mayor, it’s no surprise the 1994 municipal budget, for example, passed on a 47-0 vote. And a University of Illinois at Chicago analysis found 12 mayoral appointees on the council voted with the mayor 100 percent of the time on “key issues” between May 2007 and April 2008.

The City Council exists to provide Chicagoans with representation independent of the mayor’s office.

Allowing mayors to fill seats directly subverts the body’s purpose.

Discouraging democracy

Chicago City Council members have a powerful incumbency advantage. That’s owed to the hyper-local responsibilities of their office and low turnout in Chicago’s municipal elections.

So mayoral appointees to the Council – holding their seat for months or even years ahead of the next municipal election – enjoy an unfair advantage against opponents who don’t have the same clout.

It’s no surprise then that mayoral appointments have fueled political dynasties in Chicago. Examples include:

The Cullerton Seat: Ald. Thomas Cullerton represented the 38th Ward from 1973 until his death in 1993, when Mayor Daley appointed Cullerton’s legislative assistant, Thomas R. Allen, to fill the vacancy. When Allen resigned to become a judge, Daley appointed Allen’s brother-in-law (and Cullerton’s son) Timothy Cullerton to fill the vacancy.

The Austin Seat: Ald. Carrie Austin was appointed to succeed her late husband, Ald. Lemuel Austin, in 1994. She remained in office until 2023, when she retired following an indictment on corruption charges.

The Laurino Seat: Ald. Anthony Laurino represented the 39th Ward for nearly three decades. His daughter, Margaret Laurino, was appointed to the vacancy after he resigned due to health issues. She remained in office for 25 years.

The Mell Seat: Ald. Deb Mell was appointed to succeed her father Ald. Richard Mell following his retirement after nearly 40 years in office. She won election in 2015, and lost in 2019.

Further, mayoral appointees often lack integrity. Examples include:

Ald. Danny Solis: Appointed to fill a vacancy left by Ald. Ambrosio Medrano, who went to prison for taking bribes, Solis later wore a wire for the federal government after agents confronted him with evidence showing he too had accepted bribes, including Viagra and trips to massage parlors.

Ald. Arenda Troutman: Appointed to fill a vacancy left by the death of Ald. Ernest Jones, Troutman was later convicted on corruption charges after taking bribes from developers. An undercover informant recorded Troutman saying, “Most aldermen, most politicians are hos.”

Ald. Ricardo Muñoz: Appointed to fill a vacancy left by now-Congressman Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, Muñoz pled guilty in 2021 to wire fraud and money laundering after he stole $38,000 from the Chicago Progressive Reform Caucus.

Ald. Proco “Joe” Moreno: Appointed in 2010 to fill a vacancy left by Ald. Manny Flores, Moreno pled guilty to obstruction of justice and disorderly conduct in 2021 for reporting his car stolen when he actually loaned it to a woman he was dating.

Nothing could do more to improve Chicago’s problem with low voter turnout than changing the city’s February election timing (more on that in a future edition of The Last Ward).

But ending the clearly rigged process of mayoral appointments would be a powerful step toward reducing voter apathy and increasing trust.

Johnson’s process

For most of modern Chicago history, mayors wouldn’t even pretend to take voters’ input before filling Council vacancies.

That’s changed since Richard M. Daley, as every mayor has claimed some kind of “open and transparent process” when making their appointment decisions. Johnson will say the same.

But the problem remains.

The mayor picks the process that suits their needs. Because the mayor still holds all the cards.

So how can it change?

Johnson’s historically low approval rating could embolden City Council to reject his pick for Ramirez-Rosa’s successor, for starters. That would be an appropriate show of independence from the Council and discourage other Johnson allies from horse-trading on their own replacements.

Absent that independence or a city charter, that leaves state law.

Illinois state lawmakers should introduce and pass a bill ending Chicago’s freakish process for filling City Council vacancies, putting it in line with every other big city in the country.

Chicago voters deserve it.

✶✶✶✶

Re the mayoral aldermanic appointees who lack integrity: Don’t forget Jim Laski! Daley appointed Laski to replace Ald. William Lipinski (23rd) when he graduated to the U.S. House. As many here probably recall, Laski went on to the City Clerk’s office, which he resigned in 2006 before pleading guilty to taking $48,000 from his own friends to steer them city business in the Hired Trucks scandal. Laski used it to redo his kitchen and take his family to Disney World. When Laski negotiated a plea deal with the feds, he admitted he was involved in ghost payrolling in the early ‘90s as an aldermen, so somehow he didn’t get caught in the Haunted Hall operation but he still counts as a corrupt appointed alderman.

Fun fact: Laski used the code phrase “Go Cubs!” to tell the friend he extorted to have his wife lie to a grand jury and say the bribes were campaign donations.