How to double voter turnout in Chicago’s municipal elections

Chicago’s election timing is severely suppressing the vote.

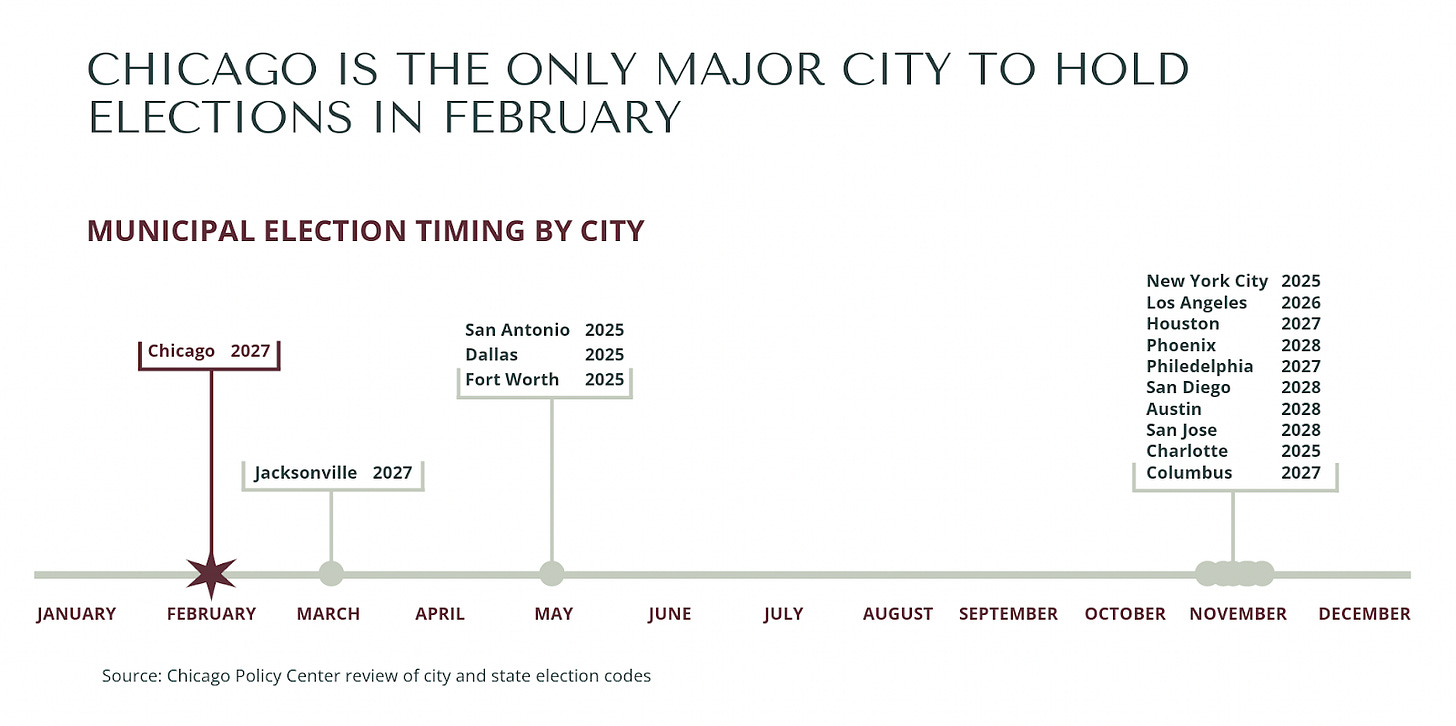

Chicago is the only big city in America to hold municipal elections in February of odd-years.

No other big city discourages voting in this way. Here’s proof.

We did a deep dive on this issue over at the Chicago Policy Center and released our research last week in the report, “How Chicago’s election timing suppresses voting.”

Here were the four most important findings:

Huge drop-off in municipal election turnout: From 2014-2024, Chicago’s average voter turnout for municipal elections was 36%. In general elections, it was 61%. That means Chicago voter participation drops by an average of 40% in municipal elections.

That drop-off is consistent across racial groups: Here’s what average turnout looked like by precinct-level racial majority from 2014-2024:

White voter turnout: 71% general vs. 42% municipal (41% drop-off)

Black voter turnout: 55% general vs. 32% municipal (42% drop-off)

Hispanic voter turnout: 49% general vs. 30% municipal (40% drop-off)

Precincts with no racial majority: 61% general vs. 36% municipal (40% drop-off)

Incredibly low turnout in certain wards: Remember, Chicago’s low turnout for municipal elections is just an average. Several wards are electing City Council members with less than 25% voter turnout.

No other reform can boost turnout like changing election timing: Transitioning to on-cycle elections is the single most significant step communities can take to boost voter participation. Major cities that have changed their municipal election timing have doubled and even quadrupled voter turnout.

Before getting into how this reform could work, it’s important to know why Chicago holds its elections in February in the first place.

Why Chicago holds February elections

There are three historical events responsible for Chicago’s municipal election timing and process.

First, Illinois’ Cities and Villages Act of 1872. After Chicago voted to operate under this Act in 1875, the city changed its mayoral election timing from November to April. Candidates on the April ballot were still chosen behind closed doors by party bosses, rather than by voters in open primary elections.

Second, the Progressive Era saw reformers push for open primary elections. A Chicago Tribune correspondent wrote in 1907 that a bill in Springfield establishing open primaries “would cause a titanic political spasm in Chicago.” But that reform would eventually pass. And on Feb. 28, 1911, Chicago held its first open, partisan primaries for a mayoral election. Most towns in Illinois still today hold party primaries on the last Tuesday of February and then “consolidated” municipal elections on the first Tuesday in April. But not Chicago.

Finally, the election of Harold Washington as Chicago’s first Black mayor led to the elimination of partisan primaries in Chicago. After Washington’s shocking upset in the 1983 Democratic party primary – in part due to the city’s white vote splitting between Richard M. Daley and incumbent Jane Byrne – white Democratic leaders pushed for the elimination of partisan primaries, believing it would reduce the likelihood of such outcomes in the future. In 1986 they tried to pass a citywide referendum establishing nonpartisan elections. But Washington forced it off the ballot with three advisory measures. In 1995 they found willing partners in Republicans who controlled the General Assembly and were embarrassed by their party’s most recent nominee for mayor of Chicago: Raymond Wardingley, a former clown performer known as "Spanky the Clown.” Republican Gov. Jim Edgar signed the law eliminating partisan primaries in Chicago.

Today, Chicago holds its municipal elections in February. And if no one receives more than 50% of the vote, there is then a runoff in April.

Changing election timing drastically increases voter participation

We took a look at major cities that had changed their election timing in recent history. The results were stunning:

Research on municipal election timing suggests transitioning to on-cycle elections is the most significant step local communities can take to enhance voter turnout. Election consolidation in major U.S. cities has been shown to nearly double voter engagement, with engagement remaining high in subsequent election cycles (Benedictis-Kessner, et al., 2023; CEDA, 2003; Durning, 2024; Dynes, et al., 2021).

In Austin and Phoenix, voter participation more than doubled after a change in election timing; in Baltimore, it increased more than 3.5 times; in El Paso, 4.5 times (Kaminsky and Weinberg, 2022). In California, contests for the Los Angeles City Council more than tripled. The average local turnout tripled among the 54 California communities that moved to even-year November elections (Durning, 2024).

Reforms like extending early voting windows and expanding mail-in voting pale in comparison to the boost in turnout that comes with changing election timing.

How to change Chicago’s election timing

Chicago should ideally establish better election timing through creation of a city charter, as is the case in many other big cities.

(Special thanks to Better Government Association President David Greising for his column on the Chicago city charter “boomlet” in the Chicago Tribune last week.)

Short of that, Illinois lawmakers should amend state law to allow for better election timing, and thus encourage more participation in local democracy.

This change could mirror the Texas model, where state law requires municipalities to pick from several uniform election dates, including those aligned with presidential and gubernatorial elections. Lawmakers could also take inspiration from the California Voter Participation Rights Act, which requires municipalities to consolidate their local elections with statewide elections if voter turnout in their standalone elections is at least 25% lower than the average turnout in the previous four statewide general elections.

Chicago deserves local leaders that represent the will of voters.

Today, those leaders too often represent voter apathy.